Article and interview by Erich Christiansen, 2009.

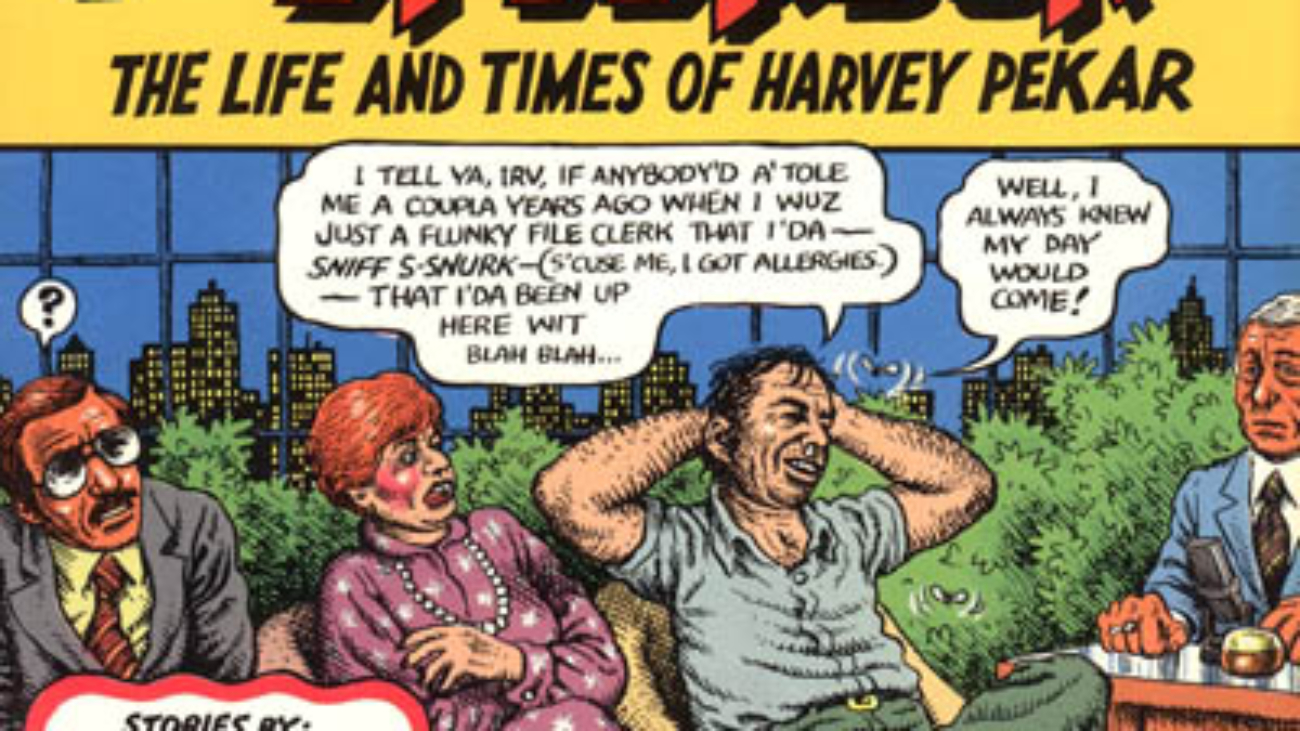

Harvey Pekar is one of the true pioneers of the comic book art form. Since the early 1970’s, his monthly series, American Splendor, along with a more recent group of graphic novels, have broken new ground—by coming down to earth. After the myth-creating fantasy of the first half of the century, followed by the frenzied taboo-breaking of the underground comix of the 1960’s, Pekar extended what comics could do by using the medium to tell stories of his own life as a file clerk in the V.A. hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. Rather than superheroes saving the galaxy, he chronicles the battles, victories, defeats, and impasses that ordinary people face in everyday life. And, as often happens in real life, his stories have no clear resolution, but instead provide a glimpse into the real moments that make up our existence.

Pekar and his work were brought to mainstream attention by a feature film, also called American Splendor, in which he was played by Paul Giamatti. More recently he has gone back in time to tell stories of his own childhood and adolescence, as in 2005’s The Quitter, which tells, among other things, the story of his life as a street fighter in tough neighborhoods.

But Pekar is no narcissist; although autobiographical, his writing is always conscious of being part of a larger world. Take, for example, Our Cancer Year, co-written with his wife, Joyce Brabner (creator of political comics, like Real War). This book chronicles his fight with cancer—while against the backdrop of the Persian Gulf War that was then taking place. As the opening lines put it, “This is a story about a year when someone was sick, about a time when it seemed that the rest of the world was sick, too. It’s a story about feeling powerless and trying to do too much…” And Pekar has used his art to tell other peoples’ stories, too. One of these was that of Robert McNeil, a black Vietnam veteran with whom Pekar worked, whose story became the subject of Unsung Hero (originally serialized in the pages of American Splendor). Pekar shows how global events intersect with individual lives. For example, in 2007, Pekar published Macedonia, the story of graduate student Heather Roberson, who goes to Macedonia to do research into how that country was able to avoid its ethnic tensions becoming an armed civil war. Her goal was to show how wars can be prevented, how violence is not an inevitable part of international politics. During her journey, she talks to various government officials and international volunteers, all working to resolve long-standing conflicts between the Macedonian ethnic majority and the traditionally marginalized Albanian minority. She gains hope from their struggles and dedication, which at the same time is tempered by the recalcitrance of age-old ethnic prejudices that she also encounters.

Pulse: Was part of the appeal of this project for you the fact that this topic dealt specifically with ethnic violence—seeing as how you grew up Jewish, and also lived in some areas and through some eras marked by racial turmoil?

Pekar: That might have been an element to it, but I’ll tell ya, what really excited me was the fact that I didn’t know a lot of this information until I met the woman that I write about. I thought it was interesting and I thought that people didn’t know it, and I wanted to bring it to their attention.

The inquiry in this book was about preventing war per se; that is, armed conflict between armed forces. But in The Quitter, you also write very eloquently about fighting on the street, to gain respect, both from others and yourself. So do you think there are parts of life in which violence is acceptable, or at least unavoidable?

I really don’t think so. I don’t think I was right in doing the things that I described. I mean, I fought to build up my reputation and stuff like that. But I should have just let people alone.

One of the parts of ‚Macedonia‘ that struck me was about the Albanian fighters giving up their arms. Because the main question was, how are they going to rely on the government to protect them when it never has before? Would you say that this reflects at all on something like the gun control issue in this country, or are they two completely different things?

I don’t know if it’s completely different, but if you’re a minority population and there’s a real danger that you’re gonna be attacked by a majority, I can see more reason for maybe wanting a gun then.

I was just thinking in terms of people who live in safe neighborhoods where they don’t feel the need to own a gun and defend themselves. It seems like it’s easier to be pro-gun control when you live in that kind of area than when you live in a high-crime area.

That’s possibly true. I can understand why you say it seems, but actually, probably more people are killed that carry guns than that don’t carry them. They’re prone to violence; they’ve already got the gun with them, if somebody messes with them, they just shoot them. I mean, in some areas, that’s kind of commonplace.

What do you think the contribution of art is to these issues? Specifically, what’s the advantage of telling this story through comics, over telling it through an essay or article? And what can comics offer that other arts forms can’t?

I don’t know if it has any advantage. Let me tell you why I got into comics. First of all, I happen to think that comics are serious, and prose and movies and television, I mean, they’re all on the same level. As I’ve often said, comics are words and pictures, and you can do anything with words and pictures.

So the reason that I got into comics, was—frankly, it had a lot to do with opportunism. I mean, by the time I started into comics, which is in 1972, I had already been a jazz critic since 1959. I had ambitions to be a bigger name and everything like that, probably a lot of people do, although not too many will admit it. I had got sick of comics when I was around eleven years old because they were so predictable, I mean, y’know, they’re for kids… the superhero stuff and that crap, so I got sick of it. But then in my early 20’s Robert Crumb moved to Cleveland, around the corner from where I lived. I became acquainted with him and I saw some of his stuff. What I was primarily interested in was meeting another guy who was a jazz record collector, ‘cuz the more jazz record collectors I knew, the more I could trade with, and the bigger collection I would have. Crumb’s roommate, though, said “Man, you really oughtta take a look at some of Robert’s work, ‘cuz it’s really good, y’know.” And more to be polite than anything else, I said “Ok.” When I saw this stuff, it was really good—it was parody, y’know? Sorta like Mad, in a way. It was good to see Crumb just tackle people directly. And then I thought, Jesus Christ, you can do anything in comics. Why shouldn’t you be able to do all kinds of stuff? Comics are used in an extremely limited way, although they’re not implicitly, limited. So I thought… o.k., realism, I mean there was no realistic movement in comics like there were in other art forms. There’s so much not done here, if I could just take a shot at something new I might get a footnote in history. But fortunately it did work out better for me than that.

You made your reputation writing about the very personal, everyday battles and triumphs. Do you think it’s especially important now, given the current world situation, to tell ordinary people’s stories in that way?

Well, I don’t know if it’s more important; it’s certainly as important. I mean, it’s autobiography, and autobiography is a big deal, whether it’s in film, or prose, or what, comics. When I started I had a few reasons for writing autobiographically. One was that, I was really interested in talking about mundane events that really could mark a person—but rarely get talked about. I thought that was one failing of comics that should be dealt with. That was one reason and another was—although I don’t know if this is anywhere near as important —before I did comics I used to be like a class clown or a street corner comedian. And I used to tell stories about myself and my friends.

I just think it’s really striking how, in your work, you don’t really have a distinction between the personal and the political. You talk about the results of these big global things, like the Vietnam War or the Persian Gulf War, but as they impact ordinary people. For example, you didn’t set out to try to tell the comic book story of the Vietnam War, but you talked to this co-worker that you had, and you got his story and preserved it.

I had special access to this guy. And he had a real interesting story, a unique story, and like a zillion other people with fascinating stories, his wasn’t told. So I thought I’d like to get this one in the books.

One thing I keep getting when I talk to people who have been through the kinds of ethnic conflicts you write about, is the stumbling block around the question of hope. There just seems to be this cynicism about whether a situation that has gone on for so long can ever get any better. And this element was present in your book too, especially when you portray people with lingering ethnic suspicions. So I guess the question is: how do you cultivate hope? I know that’s a big question, but I assume there must have been some kind of optimism that inspired you to take on this project in the first place.

Yeah, well, I guess the main hope I have is that people will finally come to their senses. I mean, I was just thinking about it, about how a multitude of ethnic groups have gotten together in the United States and for the most part, with some notable exceptions, have gotten along well. But when you have two [groups of] people fighting over the same area, it can go on for centuries and centuries. In the States, when all these people were coming from all over the world, I guess it just seemed too overwhelming to start trouble, with one group against another against another. But when two ethnic groups have been at each others’ throats for centuries, they demonize each other, and tell lies about each other.

While I was reading ‚Macedonia‘, I had Ornette Coleman’s song “Peace” in my head. That’s because of the contrast between the title and the uneasiness, the irresolution of the music. And in the situation described in the book, there’s a will toward peace, but it’s on the edge, always tentative, never quite resolved. What do you think?

I think that people are afraid to take the last step. They’re afraid to trust each other. Like this thing in, Israel/Palestine is just insane. It’s just insane! I mean, being Jewish and seeing what the Jewish people are doing over there, it’s so obviously self-defeating. And here I am being brought up to think that Jewish people are really smart and all that, and yet [over there] they’re tryin’ to lord over a buncha people who don’t like them, that never have accepted them, and that are more numerous than the Jews. Oh, it’s just insane.