By director, actor, and playwright Tim Robbins, 2005.

So here we are again. A new year faces us, a clear message has been sent to Washington – and some might say the world – by the people of the United States. Get out of Iraq. And the idiot drunk of a president says, “I hear you. So we’ll send more troops.” And the opposition parties who should be representing the voice of the American people by shouting it from the rooftops are instead talking about how they have to vote to support the troops, grumbling about the president but proposing nothing close to withdrawal. “If we don’t increase troop levels then we can always be blamed for losing the war”. And so it goes. And so we will stay. And remain targets for very angry people. There will be no voice that is standing up to say that we were wrong. There will be no apologies. There will be no reparations. We have too much invested in our lie to admit it was a lie. And so we will equivocate, and stall, and more will die, and on and on. But we will keep our pride. And we won’t show the weakness of a man apologizing. We won’t have the look on our face of the guilty being led to jail. We will not pay for our crimes in any way. No one will jeer at us from beneath the gallows. Why? Well… we meant well.

I found a letter I wrote to a friend recently. It was written on an old typewriter in late 2001. I don’t know why I wrote it on a manual typewriter. Maybe I wanted to go backwards, find a Luddite inspired way to proceed.

Here it is:

Greetings from our wounded city. I hope the road has treated you well and that you are healthy, happy and loved. This has been a wild and disturbing few months since I saw you last. I was in L.A. when the madness happened, drove home the next day, made it in 2 days. What a terrible feeling to be so far away when something so catastrophic happens a mile from your children. They, like so many kids in New York, I suppose, have had terrible dreams and a perspective now on life that is unlike anything we grew up with. I was watching something with Miles and the actor said something about a future where our children are safe and Miles, his voice dripping with cynicism, said, “That would be nice.” Eva, my 16 year old was trapped in Brooklyn on the 11th. They had closed the bridges and she couldn’t get home from school. Jack wept and worried when the next bombs would come. Susan lost a very good friend in one of the planes, made all the more horrible by actually witnessing her death from the street. When I got back from L.A. I went to volunteer, wound up cooking burgers for relief workers, met people from all over the country who had gotten in cars the moment it happened to be here to help. People were sleeping in cots in shelters, or in their cars helping in whatever way they could, often for 20-hour shifts. I was really inspired by the sense of community, of collectivism, of the unified focus to help, to survive, to persevere. Later that week I went down to Ground Zero to serve food there.

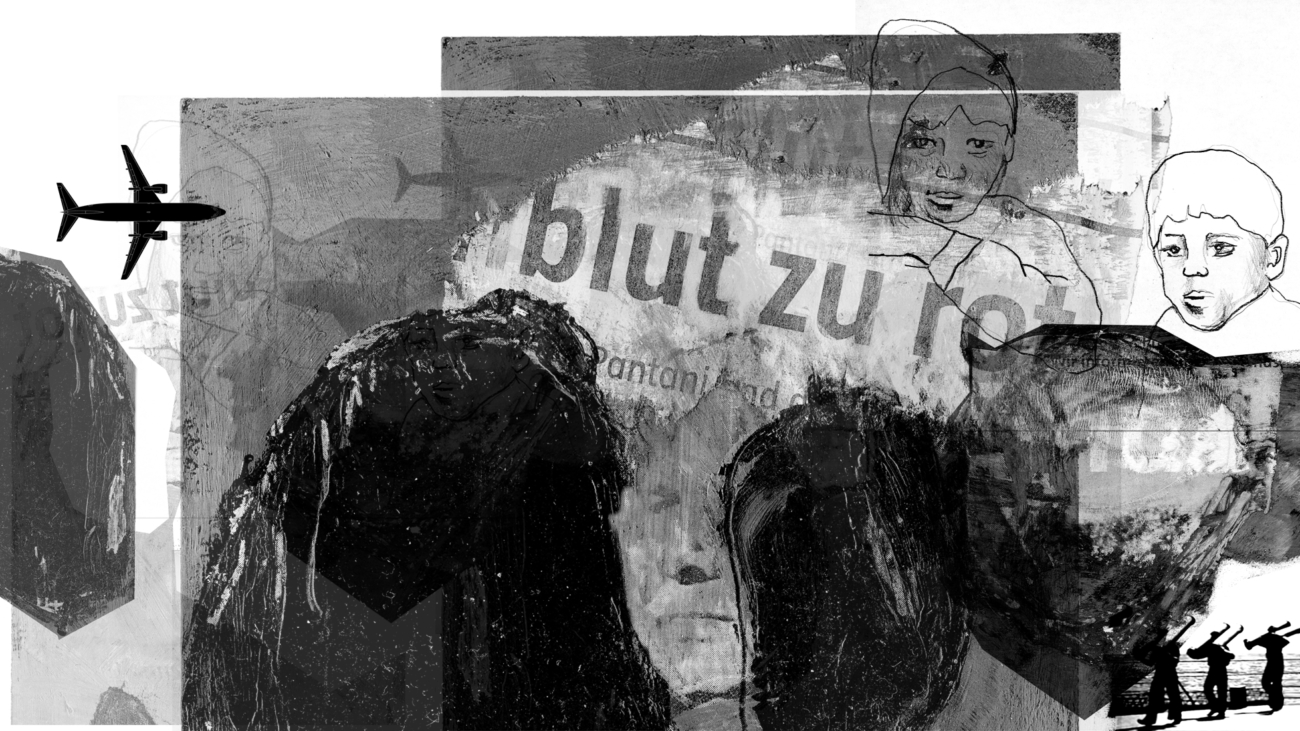

The scope of the thing was immense. The size of the area of destruction, the smell of burning toxins, steel, flesh, the tempest in the eyes of the volunteers who had pulled too many body parts out of the rubble, who had lost friends, brothers, fathers, and were still searching vainly for survivors, the collective anguish, the life stories of thousands floating in the fetid air, unspoken. The city carries a heavy weight, millions with a subconscious unable to grasp what it is to witness mass murder, others wanting to forget, still others carrying a dangerous, dormant fury. It has been disheartening to see this wonderful sense of community begin to dissolve into arguments over who deserves how much from which relief funds, as unity degenerates into fodder for politicians speeches, for heart tweaking advertisements. I get a terrible sense of foreboding as we move away from the generosity and compassion of the moments after the tragedy into a strange new moment. We are now marketing our grief. I’m afraid we are losing something precious. In using our grief to sell products, and worse, war, we are trading in our soul for… what?

At the time, writing this above, I didn’t know what we were trading our soul in for. I’m still not sure. But what I’ve come to realize is that it wasn’t us that were trading in anything. Our leaders were the clear brokers of that deal. And they didn’t just trade it in. They made an industry of our grief, so much so that I’m sure you’re already sick of me dredging up my emotions of that time. I don’t blame you. I don’t think Bush or Blair or Guliani or McCain has been able to utter three sentences in a public speech without bringing up that fateful day. Poor poor pitiful us. 9-11 9-11 9-11. A litany, a chant, that has led to the moral righteousness you now see us spreading throughout the Mideast. Observing the behavior of our leaders in the past few years I am reminded of when my children were younger, of the fear-based worldview of the pre-pubescent, the terror of middle school, the hysteria and gossip, the black and white morality, the inability to accept responsibility, the hateful divisions, the ‘with us or against us’ schoolyard tussles. In this post 9-11 world, in a time when we have needed mature, levelheaded, adult leadership, we have been led instead by a screaming pack of hysterical prepubescent girls (with all apologies to hysterical prepubescent girls).

Christopher Isherwood once wrote: “The Europeans hate us because we’ve retired to live inside our advertisements, like hermits going into caves to contemplate.” That certainly has been true for the past 6 years. But instead of contemplating our possessions, our way of life, we have been contemplating our grief. The advertisements worked on us and we bought the product day after day. The top rated television show, ’24’, posits a world of constant threat of terrorist attack. Our leaders and our media don’t talk of hope and inspiration but of fear and cynical distrust. An illusion has been created, much like the illusions that kept Big Brother in power in Orwell’s 1984. We have now come to live in our fiction. But the real world is entirely different. I had a unique opportunity to discover this in the lead up to the Iraq war. Having openly spoken out against the war I was roundly attacked in the media. Newspapers, television pundits called me, and others who had the temerity to question the administration, traitors, Saddam lovers, terrorist supporters, anti- Semites. The cacophony of voices was quite intimidating and had I lived in a rural or suburban area I probably would have been cowed into silence. But I live in New York and had to face this hatred directly on the streets. Or so I thought. What followed in the weeks and months following this media excoriation opened my eyes to a disturbing truth. Everywhere I went I was met with support. Whether it was the “God bless you. Keep talking” from the old woman on the streets of New York or the “Give ‘em hell, Tim We’re with you” from the redneck at the state fair in Florida, I came to realize that the real voice of the United States was opposed to this war from the start, or if not opposed to it, at least mature enough to support another person’s right to oppose it. The real American citizen understood that debate and dialogue were necessary before such an important decision. But there could be no debate when there were so many lies floating about. Only now, as the child-like hysteria and shrieking panic has died down, and as more adults try to take the dangerous toys out of the children’s hands, have we come to understand that this war was a terrible idea sold by a very small amount of neoconservatives through an enormous megaphone. The only majority these ideologues ever had was in the media: all the networks, all the major newspapers, all the cable news programs acted as the advertising arm of the government in selling this war. The American people were inconsequential. They weren’t part of the equation. They were sold an illusion and were cowed into silence by intimidation. In the ensuing years those people have slowly and steadily found their voice and the courage to use it again. And so we see the results in our recent elections. And from the chattering classes come phrases like “democracy works” and “the people have spoken”. The democrats talk of raising the minimum wage and fixing the health care system. But it would be a grave mistake for the people of the United States to believe that their real voice has been heard. We are, despite the recent vote, still living in our fiction. We are still living in Orwell’s Oceania, where truth has been turned on its ear, where black is white, day is night, and ignorance is strength. We live in a country that allows impeachment for a president that lied about an extra marital affair but reacts with contempt at the idea that lying about war is a punishable offense. The hundreds of thousands of dead, injured, and uprooted by this unnecessary invasion should just get over it. We meant well. There is no crime in lies that lead to death, only in lies that lead to semen stains. As long as this fiction, this absurd, diabolically criminal fiction is accepted we will remain in our prepubescent hysteria, wallowing in the pit that we allowed our leaders to dig us into, looking up at a mountain of twisted steel, breathing in the smoldering acrid air of our own failure, our own betrayal of our better adult.